Digital Pathology has had a difficult gestation period. Some regions have made strong progress and embraced digitisation. However, compared to other diagnostic market segments, both investment and uptake has been underwhelming. There are several reasons for this, ranging from the complexity of the segment, with physician education, legislation, new infrastructure and changing models of diagnostic care all needing to be put in place before mass adoption is a possibility.

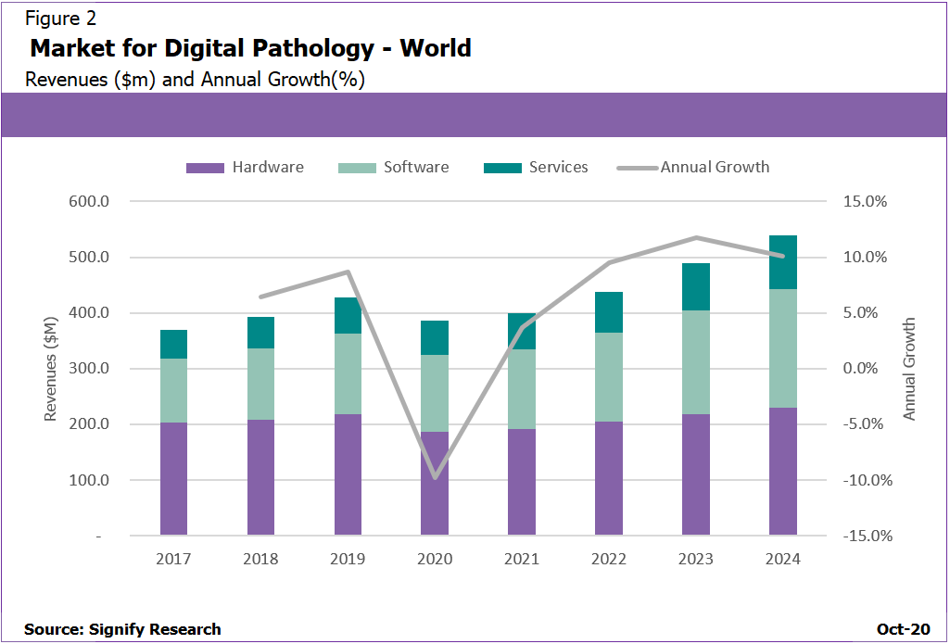

As shown in Signify Research’s 2020 Global Digital Pathology report, however, there is great long-term potential for the digital pathology market. There are also several key insights that can be gleaned about the developing sector

Investment in the market is changing

Around a decade ago, most of the investment that was being made into the digital pathology market focused on scanner hardware, the epitome of which was Roche’s acquisition of Ventana Medical Systems in 2008 for a $3.4bn. This was the established pattern for some years, with the market ultimately consolidating around a few leading vendors such Roche, Philips and Leica.

The following period, from around 2012 to 2017, in a sign of the infancy of digitalisation in the sector, headline-grabbing levels of investment fell. Instead there were a number of small seed and series A funding rounds in AI tools and software, rather than hardware.

Then, in 2018, there was a dramatic increase in investment. Funding came in as investors became more confident in the opportunity presented by digital pathology, while approvals, such as the FDA giving the green light to Philips for primary diagnosis with whole slide imaging, also helped ease the path.

Figure 1: Funding increased dramatically in 2018 after a relatively slow period

This uptick meant that in 2019 the amount invested into digital pathology companies approached $250m, an almost ten-fold increase on the figure from just two years earlier. Is this a trend that seems likely to continue? Signify sees two possible outcomes. In the first, digital pathology adoption increases over the coming years, bringing with it a second wave of investment, and maturation of investment for leading companies. The other, more pessimistic outcome is that seed and series A vendors struggle to gain a significant return from what is currently a relatively small market. This would precipitate a stagnation or even decline in investment over the near term. Both are possible, but of these scenarios, a short-term slowdown in investment seems most likely, ahead of wave of investment or vendor consolidation.

AI tools are becoming more feasible

Forecasting the future of nascent markets is always a challenge, and the progression of AI in pathology is no exception, however the nature of a pathologist’s work, which involves extensive identification, quantification and classification, means the feasibility of it being supported by an AI-based software toolset is increasing.

There are several factors that are driving this trend, which also ultimately indicate the potential for AI tools in digital pathology. One of the most significant is the declining reimbursement for pathological services, despite the demand for testing increasing, which is rapidly increasing the strain on pathologist resources. As with other fields both within medicine, and also in other industries, AI tools have the potential to speed up workflows by reducing simple, repetitive and time-consuming tasks. In pathology this could mean streamlining quantification and manual reporting, for example, to improve the efficiency of a diagnostic workflow. AI-based triage can also prioritise pre-classified cases in pathologist work lists, so the cases that are most likely to be positive, i.e. the patients that are most likely to require care most urgently, can be dealt with soonest. As well as workflow improvements, by speedily getting treatment to those who need it most, AI-based triage also has the potential to improve clinical outcomes.

In a similar vein, as well as increasing the efficiency of diagnosis for individual patients, AI tools present the opportunity to counter the shortage of consultant pathologist resources and increasing demand in mature markets. What’s more, in other, less developed markets, these new tools, alongside telepathology technologies, could help provide pathology services for patients in remote areas and other places where technology and trained pathologists are scarce.

Beyond the efficiency improvements, AI-based pathology tools can also help improve outcomes by facilitating more accurate diagnosis. Presently, in certain specific roles, AI tools are operating at a comparable level of accuracy to their human counterparts, so, in the near term, it is likely AI will take over some of these tedious tasks, enabling the pathologist to focus on diagnosis and reporting.

There are factors that will hinder the adoption of these tools. Some are specific to AI, such as a limited supply of training data due to the slow adoption of digital pathology technology, the significant amounts of processing power and the upgrades to IT systems needed to run the software, and the difficulty of integrating the systems with existent services. Other problems are more universal: The cost, which can seem especially high given the smaller budgets of pathology services compared to other departments, and the regulatory stringency.

The increased feasibility of AI-based tools, as well as the many opportunities they offer in a path lab, means that over time they will become more mainstream; however that is unlikely to happen in the near to medium term, a significantly slower adoption curve versus other sectors such as radiology and oncology is forecast.

Digital pathology in different geographies

Different geographies are adopting digital pathology at very different rates. There are a few reasons for this disparity, but chief among them are regulatory differences between regions. The clearest example of this is the US market.

Despite being the largest regional market globally, digital pathology adoption remains relatively low. This is, in no small part, down to the fact that fact that all clinical solutions in the USA used for primary diagnosis must be sold on a “closed loop” basis, with a scanner and viewer provided from the same system. This regulation weighs on the technology’s journey to ubiquity. Most use has therefore been tied to secondary purposes, such as clinical review or telepathology consulting.

Contrast that with some of the European countries with less restrictive regulation for primary diagnostic use and it’s clear there is great potential for the rollout of much more thorough services. In Denmark, for example, all pathology tests are managed via a central, national laboratory information system (LIS), while the country also maintains a national digital database of all pathology reports created since 1998.

Beyond a more simplistic look at which regions and countries have deployed more or less digital pathology tools, Signify’s report also identifies the differing adoption strategies of different regions. Broadly, these fall into two categories. There are countries, such as in the USA and Canada which have a more piecemeal digital pathology adoption strategy, where, because of regulation and other factors, relatively small parts of the pathology process are digitised individually. The conversion to digital pathology technologies is more gradual and incremental. The other strategy, which is often preferred in Northern Europe, is to digitise whole swathes of pathology infrastructure in one instance, creating more integrated systems, as in Denmark, the UK and the Netherlands for example.

Software is becoming hardware agnostic

One area of growth within the digital pathology market is the software side, which is forecast to outperform the hardware side by a considerable amount with a forecast CAGR of 11.5% compared to 5.4% respectively. A significant portion of this growth comes from increased focus from health providers on enterprise pathology image management, wider availability of “scanner agnostic” software platforms and a new generation of scanners that produce DICOm-standard pathology images; this increasingly allows software and hardware to be sold discreetly.

In these areas, investment is being made as software-only outfits are developing and offering bespoke pathology solutions, which can be used on hardware from multiple vendors. In addition to these best-of-breed solutions, some bigger radiology and clinical informatics vendors are also wading into the market and driving growth. These larger companies are aiming to challenge the bespoke players, insisting that more common solutions, which centralise image management across multiple clinical departments, are the preferable option. This dichotomy is set to form one of the key battlegrounds in digital pathology over the coming years.

Figure 2: Software revenues are not only increasing, they are becoming a higher proportion of total revenues

While this separation of hardware and software is primarily happening in areas outside of North America, where regulations allow vendors more flexibility in selling their products, even in the USA, the link between hardware and software is being severed. The Sectra-Leica 510k approval was the first example of a separate hardware and software vendor receiving FDA approval for a combined solution. The approval did rely on Leica Biosystem’s existent 510k clearance for its Aperio AT2 DX scanner, with the Sectra Digital Pathology Solution representing an extension of the clearance rather than an entirely distinct approval, but it does mark an important milestone on the way to hardware agnosticism.

The digitisation of pathology is lagging behand other areas

Currently, pathology has a low level of digital maturity. Like several other sub-specialities, such as genomics and surgery, pathology sits within a “second wave” that is relatively slow to transition to consolidated and interoperable digital software.

There are numerous reasons for the sluggishness of these second wave ‘ologies’ but there are also several common characteristics that they share. Complexity and specialisation are demanded, such is the nature of the applications, however, each also has a highly fragmented and complex market. There was some initial consolidation by the leading hardware vendors, but since then there have been fewer competitive mergers and acquisitions. This is compounded by the fact that there are many different facets of histopathology beyond scanning and reporting, such as staining and preparation equipment and lab equipment. Adding further complexity to the market is a wide variety of best-of-breed specialist software tools. All of this together has meant that pathology is a particularly difficult segment for new vendors to enter.

As mentioned earlier, regulation of digital pathology is stringent and has a significant impact on the segment. This is particularly keenly felt in North America, despite its status as the largest health technology market, where the need to regulate the entire ‘pixel pathway’ by considering the scanner and viewer as a single device has made it difficult to establish models that ‘de-couple’ scanner hardware and software.

On top of all of this, the aforementioned best-of-breed software focus, which can trace its roots to the influence of early adopters in research-level academics, has meant that few central software platforms have been able to flourish.

One way of illustrating how far digital pathology is lagging behind the digitisation of other diagnostic specialities is by comparing the world annual spend on IT software by application. In 2018, for example, around $2.3bn was spent on IT software for radiology, a figure dwarfing the $125m or so that was spent on pathology software. Ultimately this means while some areas have already reached, or are on the cusp of reaching digital maturity, such as radiology and cardiology, digital pathology is only in the very early stages of adoption, with maturity not being forecast for 10 or more years, long after radiology, cardiology, breast imaging and oncology.