By Mark Clements, MD, PhD, and Sarine Babikian, PhD, MS |

In recent years, there has been a great deal of talk in healthcare circles about remote patient monitoring (RPM), a trend that has only accelerated over the past 18 months with the arrival of COVID-19 and the need, early in the pandemic, to transfer a great deal of care to remote delivery. Yet despite all the conversation, the actual adoption of RPM technologies points toward the truth that RPM usage, for the most part, is still in its infancy. According to one recent survey of hospitals and clinics, only 20 percent have implemented some kind of RPM solution.[1] Similarly, a 2020 member survey of the American College of Physicians revealed that just 24 percent of practices have RPM technology available, a rate that the report on the survey’s results notes “is somewhat lower than other technologies.”[2]

In recent years, there has been a great deal of talk in healthcare circles about remote patient monitoring (RPM), a trend that has only accelerated over the past 18 months with the arrival of COVID-19 and the need, early in the pandemic, to transfer a great deal of care to remote delivery. Yet despite all the conversation, the actual adoption of RPM technologies points toward the truth that RPM usage, for the most part, is still in its infancy. According to one recent survey of hospitals and clinics, only 20 percent have implemented some kind of RPM solution.[1] Similarly, a 2020 member survey of the American College of Physicians revealed that just 24 percent of practices have RPM technology available, a rate that the report on the survey’s results notes “is somewhat lower than other technologies.”[2]

The slow uptake of RPM could be due to a number of misconceptions some healthcare leaders might have about the technology and practice of RPM. The first and most fundamental may be about its definition, as many people seem to use RPM interchangeably, albeit somewhat imprecisely, with the term “telehealth.”

The broader term, telehealth, simply refers to the healthcare professional’s use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to provide care. Most familiar are the phone and video appointments that overnight became seemingly ubiquitous with the advent of the pandemic. But true remote patient monitoring is a more specific discipline within telehealth.

RPM refers to both the information technology and the practice a provider uses to gather patient-generated data outside the traditional clinical setting, make assessments about the patient’s progress based on those data, and if necessary, intervene via communications technologies, including telehealth, to make treatment adjustments that will keep the patient on track toward improved outcomes.

RPM can be an incredibly useful and effective practice for managing the health and care of patients, especially for those living with certain chronic conditions. But to get more healthcare leaders comfortable with thinking seriously about pursuing and implementing RPM, it may help to clear up four more misconceptions.

“RPM is really just to cover for when patients can’t make it in”

After clearing up the sometimes murky definition of the phrase, another important misconception about RPM is that its primary usefulness is to follow patients when they can’t easily make an in-office visit, such as when they live remotely or when special circumstances dictate, like during the pandemic.

But in the case of chronic diseases like diabetes, where a patient frequently generates data that serve as day-to-day health indicators, the main role of RPM isn’t to just serve as a stop-gap until an in-office visit is possible. The true value of regular remote monitoring of patient data (e.g., weekly or biweekly) combined with as-needed telehealth coaching is to provide just-in-time care, or precision engagement, that keeps patients on track to achieve better patient outcomes than are possible without it.

Using diabetes as an example, the ability to use RPM regularly to help fine-tune a patient’s chronic care regimen could mean intervening on occasion just to make simple diet or medication adjustments. Brief interventions over time, however, can result in significant longer-term improvements in a patient’s health outcomes, as is being demonstrated by a growing body of clinical and real-world evidence. Our team reported on one example of the latter earlier this summer at the annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association.[3]

Our poster presentation was focused on a real-world study we conducted of 424 middle-aged people with type 2 diabetes (ages 42-59) whose health care professionals at 11 different U.S. diabetes care centers used the RPM component of an integrated diabetes data platform to regularly monitor the results generated by their patients’ glucose monitoring devices. As a result of their RPM activity, the care teams were able to identify patients with deteriorating glycemic control and deliver timely telehealth interactions outside of the patients’ routine clinic visits.

Interestingly, what we found is that the population demonstrated not only immediate but also sustained glycemic improvements that were statistically significant (all Ps < .05) not only for three different glucose measures, but also—notably—at every interval studied (3, 6 and 12 months from baseline).

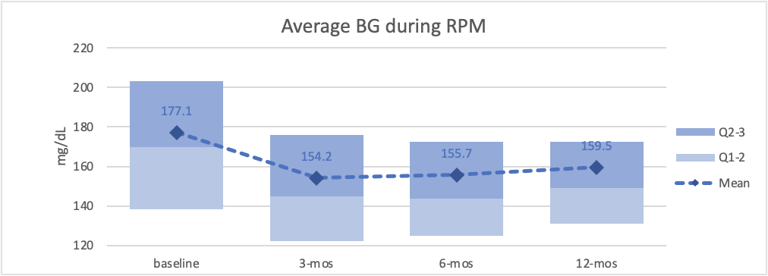

- We saw a decrease in average glucose levels across all three intervals of approximately 12% or a glucose value of 20 mg/dL. (Figure 1)

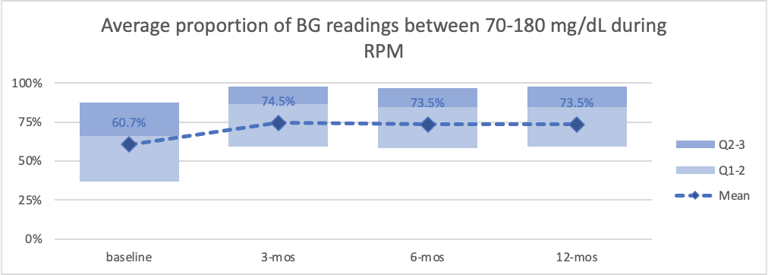

- We observed an increase—immediate and sustained—by roughly 22% in the population’s average proportion of their glucose readings that were within the acceptable range (70-180 mg/dL). (Figure 2)

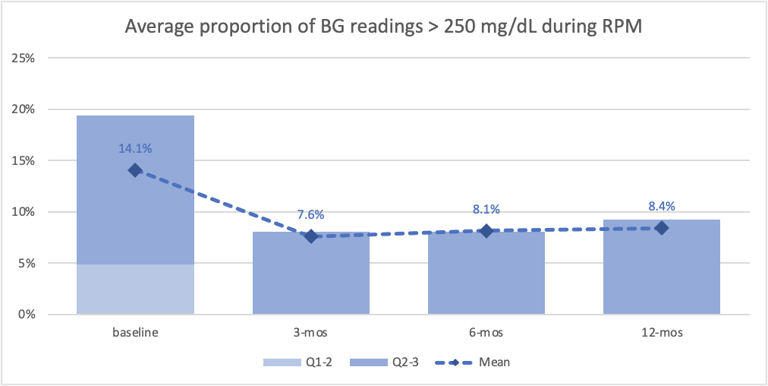

- And we saw the average proportion of high glucose readings (>250 mg/dL) decrease across all three intervals by 42% on average. (Figure 3)

Figure 1—Average blood glucose levels during remote patient monitoring. Credit: Glooko Inc.

Figure 2—Average proportion of blood glucose readings that were in range (70-180 mg/dL) during remote patient monitoring. Credit: Glooko Inc.

Figure 3—Average proportion of blood glucose readings that were high (>250 mg/dL) during remote patient monitoring. Credit: Glooko Inc.

In addition to real-world studies like ours, there are also randomized controlled trials studying RPM that are producing demonstrable outcomes. In fact, sticking with our example of diabetes, some demonstrate that patients whose care incorporates RPM and coaching are experiencing significantly greater improvements in glycemic control than patients in the control groups, who are essentially receiving the current standard of care, which is quarterly in-office visits.[4]

This is not to argue for swapping out in-office visits for RPM and telehealth coaching. Rather, it’s a case favoring the integration of regular RPM and coaching with conventional in-office care. It’s a testament to what’s possible when providers have a running understanding of what’s happening with a patient’s self-care between appointments and can intervene more quickly to keep patients on track, rather than having to wait every three months to find out just how far a struggling patient may have gone off the rails.

“There’s really no patient demand for RPM”

Another misconception that can lead healthcare administrators to vacillate when considering RPM adoption is the belief that while it may eventually become a necessity, there’s no current patient demand that makes implementing RPM a pressing concern for most clinics and healthcare facilities.

If what patients say is any indicator, that lack of concern is unwarranted. A study of 300 consumers released in June by the research firm MSI International found that 80 percent of Americans favor RPM and nearly half are very favorable about incorporating it into medical care. In this study on perceptions of RPM, between 36 and 43 percent of respondents said it offered efficiency, accuracy, and greater convenience, and they said it also provides peace of mind and more control over their personal health.[5]

An even larger concern for mainstream clinics and healthcare systems is that patients who are ready and willing to go for RPM aren’t waiting for conventional healthcare providers. There is a whole new generation of innovative startup disease management platforms whose entire business models are based on providing remote monitoring and virtual coaching, especially to patients who are living with chronic conditions. They’re noted for their greater appeal to patients because they provide a coaching and disease management experience that is more automated, more personalized, and in real-time.

These alternative disease management providers are also incredibly well-funded, with venture capitalists and other investors who view them as the future of chronic care standing by, ready to invest. According to the Financial Times, the number of significant investor deals (i.e., >$2 million/deal) made in US digital health companies reached nearly 600 in 2018 alone, an annual toll that had more than quadrupled what it was just seven years prior.[6]

Perhaps most startling of all is that these new platforms built around RPM and coaching models are quite prepared to do an end run, not only working directly with patients but, if the patient so chooses, completely outside of the patient’s relationship with their primary physician.

While RPM is only part of the answer and is best if integrated under the umbrella of the larger care strategy of a patient’s primary provider, the fact remains that patients are actively interested in and ready to pursue RPM. At the same time, when conventional clinics and healthcare systems aren’t prepared to respond, alternative RPM providers are already standing by, ready to move in to fulfill the demand.

“RPM would be nice to have, but it probably wouldn’t be compatible with our systems”

Another misconception that healthcare leaders should free themselves from is the idea that if they adopt a new RPM technology, it might not be compatible with their existing EHR or that they might have to simultaneously upgrade their EHR.

Clearly, it’s important for an RPM system to be compatible and to communicate seamlessly with the EHR to ensure that all RPM data and transactions benefit from the key features of the EHR, from improved data accessibility to charge capture and preventative health. And the last thing clinics and healthcare facilities need is to invest in an RPM system where a patient’s information won’t easily flow into the EHR.

However, at this point in the history of RPM, there are clearly systems available that are not only compatible with current EHRs but also backwards compatible with popular legacy EHRs. What’s key is that clinics and systems interested in pursuing RPM find an appropriate partner and that they work closely with the partner through the planning process to ensure a smooth integration with the EHR. It’s also important to select a partner that not only has compatible technology but who will also assign staffing to ensure there’s both an integration strategy as well as personnel to optimize the integration.

EHR compatibility is not something that needs to stand in the way of pursuing an RPM system, but selecting the right RPM partner is vital to ensuring a smooth integration.

“From what I’ve heard, RPM really ends up just being an endless cost center”

The final misconception healthcare leaders have regarding RPM has to do with what always seems to be the final hurdle. As the saying goes, it all comes down to money.

However, with RPM systems, though it used to be true, it would now be incorrect to assume that you can’t have a financial win-win. It used to be that you would adopt RPM technology to help better manage your chronic care patients, but ultimately, the expenditure of purchasing and installing RPM technology as well as the actual use of it would always prove it to be a cost center.

As always, if your physicians use RPM to manage chronic care patients and keep their health metrics in check, you will probably realize significant cost savings. That just comes with keeping them healthy and not needing to utilize cost drivers like the ER or hospital admission.

But in just the past few years, something happened that made the economics of RPM an even bigger story than just savings. In 2018 and 2019, CMS began issuing and accepting CPT codes to reimburse not only for the RPM activity of collecting patient data but also for the provider’s time spent counseling patients to make therapy adjustments.

The reality is that, in the last few years, RPM services have evolved right before our very eyes from a cost center into a revenue stream. Now this means that, at budget time, chronic care programs that for years have had to come “hat in hand” now can come delivering revenue while at the same time effectively managing their patients.

Surprisingly, we continue to meet healthcare executives who, because they are not aware of these CPT codes for RPM, are also not aware that not only do their chronic care programs have the wherewithal to sustain themselves but they also have the ability to deliver revenue back to the organization.

In healthcare, it seems there are always new hurdles we have to deal with, hurdles that seem to keep us from advancing in new and better ways to help the patient. Hopefully now, with a better understanding of what’s true and what’s not, RPM will be one of the exceptions that makes it out of the gates and gets healthcare delivery organizations on their way to delivering care that is more patient-friendly, self-sustaining, and better at improving and sustaining patient outcomes.

[1] More Than Three-Quarters of Hospitals Anticipate Remote Patient Monitoring to Match or Surpass In-Patient Within Five Years.; 2021. Available at: www.vivalink.com. Accessed August 16, 2021.

[2] 2020 ACP Member Survey about Telehealth Implementation. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2020:6. Available at: www.ACPonline.org. Accessed August 16, 2021.

[3] Sheng T, Babikian S, Singh V, Clements, MA. 467-P: Immediate and Sustained Trends in Glycemic Control during Remote Patient Monitoring in People with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2021;70(Supplement 1): -. https://doi.org/10.2337/db21-467-P.

[4] Sheng T, Parks L, Babikian S, Singh V, Greenfield M, Clements, MA. 861-P: Glycemic Improvements following Mobile-Enabled Remote Patient Monitoring: A Randomized Control Study. Diabetes. 2020;61(Supplement 1): -. https://doi.org/10.2337/db20-861-P.

[5] MSI International Study: Americans View Remote Monitoring of Health Favorably.; 2021. Available at: www.msimsi.com. Accessed August 16, 2021.

[6] Kuchler H. How Digital Health Apps are Leading the Fight Against Diabetes. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/0fee5b5c-a357-11e9-974c-ad1c6ab5efd1. Published 2019. Accessed August 16, 2021.

About the Authors

Mark Clements, MD, PHD, CPI, FAAP, is Chief Medical Officer at Glooko Inc, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, and a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, where he serves as Director of Pediatric Endocrine/Diabetes Clinical Research. He is also a clinical researcher of new diabetes treatments and technologies, having served as principal investigator or co-investigator in more than 30 clinical studies and patient registries.

Mark Clements, MD, PHD, CPI, FAAP, is Chief Medical Officer at Glooko Inc, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, and a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, where he serves as Director of Pediatric Endocrine/Diabetes Clinical Research. He is also a clinical researcher of new diabetes treatments and technologies, having served as principal investigator or co-investigator in more than 30 clinical studies and patient registries.

Sarine Babikian, PhD, MS, is a Senior Data Scientist at Glooko Inc. Her doctoral studies in mechanical engineering focused on the coordination of multi-muscle systems. Concurrent to that research, she served as Research Assistant at University of Southern California, where she designed human data collection experiments using electroencephalography (EEG), load cells, accelerometers, electromyogram (EMG) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). At Glooko, Dr. Babikian manages data analytics, algorithm development, and data products.

Sarine Babikian, PhD, MS, is a Senior Data Scientist at Glooko Inc. Her doctoral studies in mechanical engineering focused on the coordination of multi-muscle systems. Concurrent to that research, she served as Research Assistant at University of Southern California, where she designed human data collection experiments using electroencephalography (EEG), load cells, accelerometers, electromyogram (EMG) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). At Glooko, Dr. Babikian manages data analytics, algorithm development, and data products.